Phylogenomics and species delimitation of Crowned Snakes (Tantilla)

At the Florida Museum of Natural History, along with collaborators at the Smithsonian, we are working to resolve the taxonomy of the southeastern crowned snakes (Tantilla)—a group of fossorial, centipede-eating snakes native to the southeastern United States.

Our preliminary analyses show that traditional, morphology-based classifications are deeply discordant with patterns of genetic structure. In fact, both subspecies- and species-level classifications seem problematic in light of molecular data. To resolve the relationships among the snakes in this group, we are using genome-wide sequencing data to test species boundaries and establish a stable, well-supported taxonomy.

We also place these genetic patterns in a historical context. Pleistocene sea-level fluctuations repeatedly fragmented the habitats across the southeastern United States, which resulted in repeated isolation and range expansion of Tantilla populations. Untangling the resulting history—which likely involves introgression and ongoing gene flow—will help explain how the diversity in Tantilla evolved in the region.

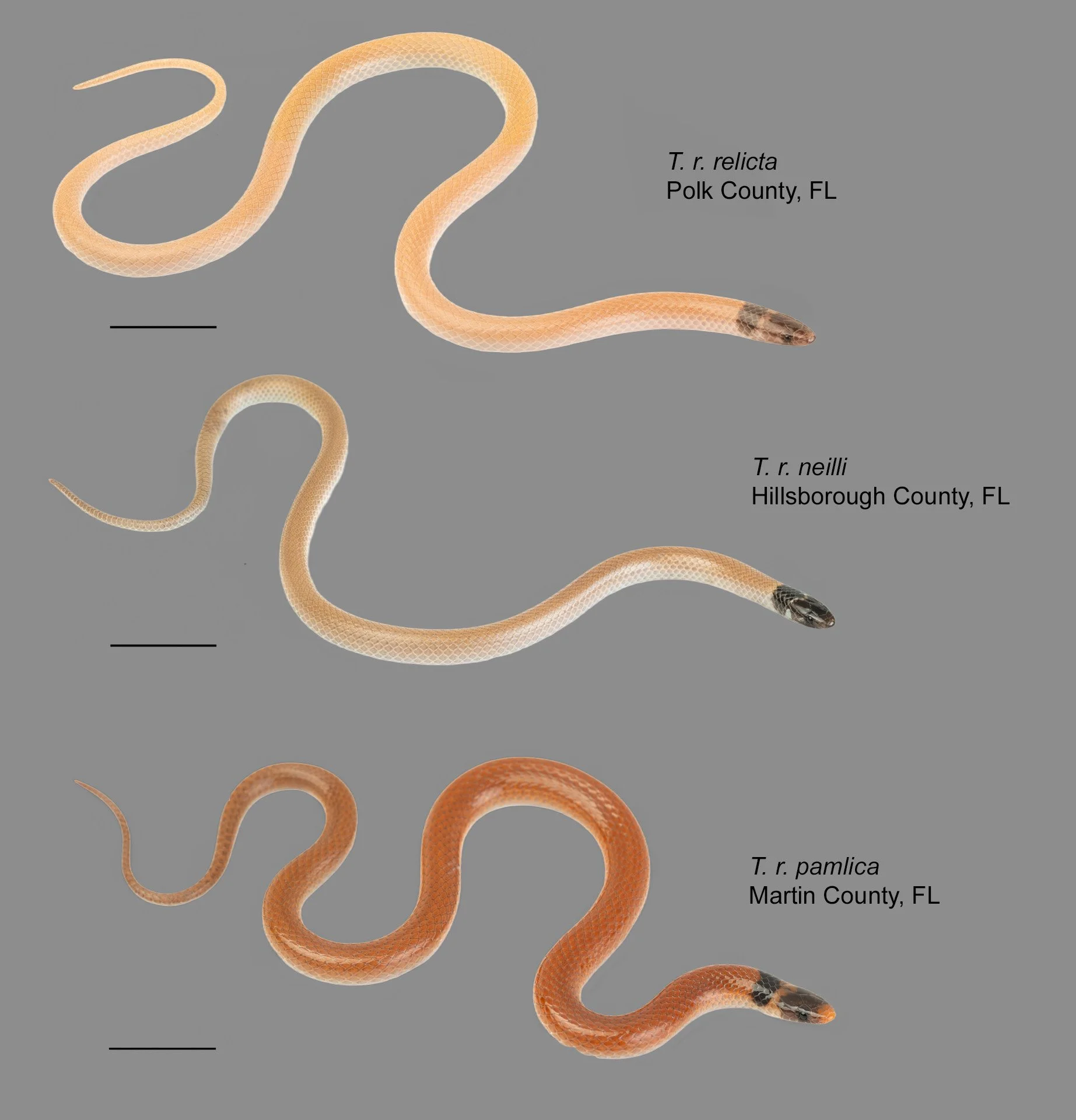

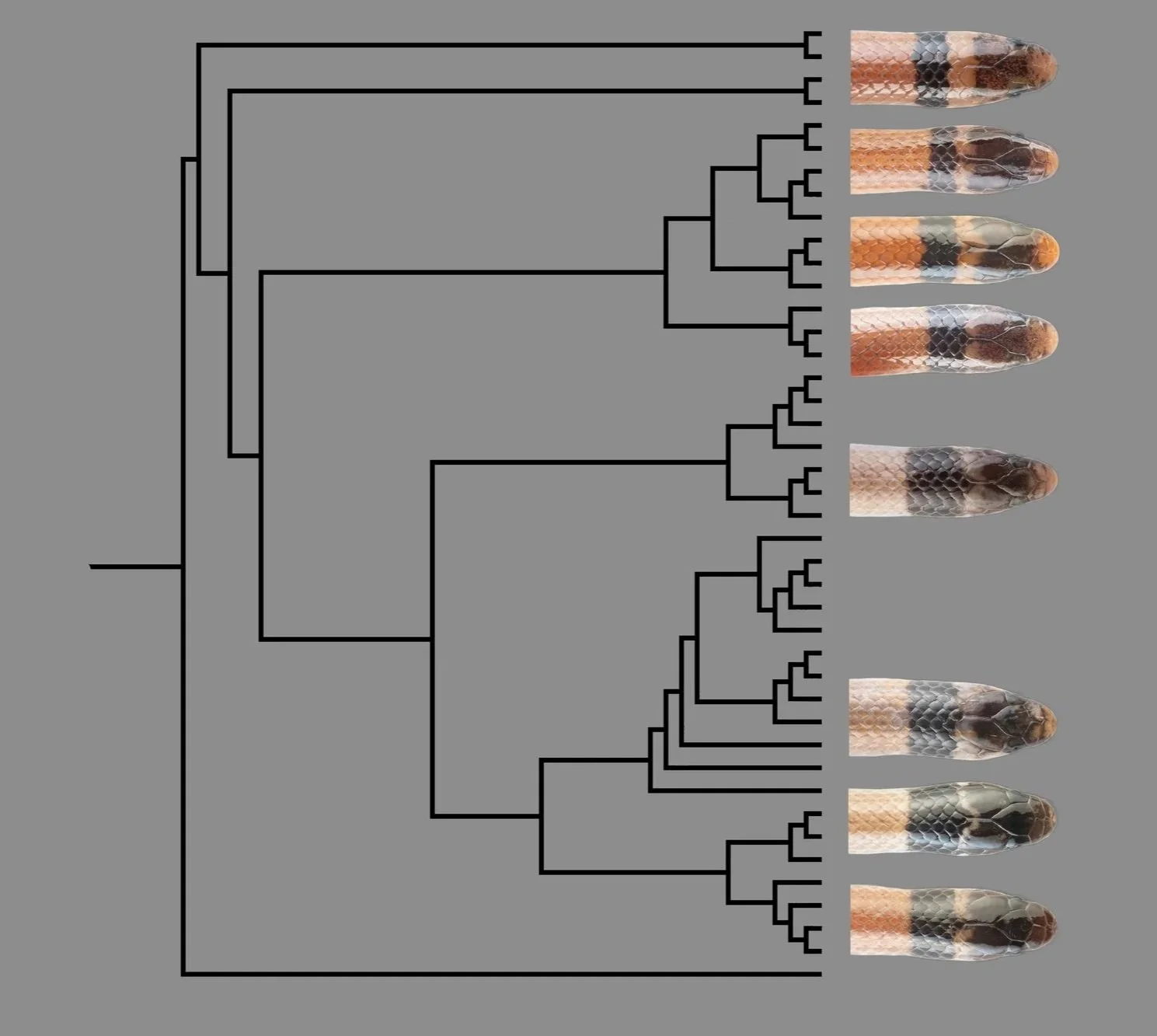

Nuchal patterning was one of the primary characters used to diagnose different taxa within this group. We now know that evolutionary relationships poorly explain the variation in this character, but it is still interesting to visualize. At left are photos of snakes I collected across the range of T. relicta to illustrate the variation once used to diagnose these snakes on a preliminary mitochondrial phylogeny. We hope to unravel the taxonomic incongr

This project has involved countless hours of fieldwork to address sampling gaps across Florida and adjacent states. Collecting Tantilla can be difficult, and when there’s little cover (rocks and logs) to flip, we often resort to simply digging in the sand. It’s a tedious but rewarding process, and it gives us the opportunity to collect other secretive psammophilic species, like mole skinks (Plestiodon egregius).

In collaboration with Nanjing Forestry University and Hainan Normal University, I have worked on multiple projects advancing our understanding of China’s herpetofauna. Through both independent and team-based fieldwork, I have helped discover putative new species of Megophryid frogs and Natricine snakes, find province-level distribution records for hynobiid salamanders, and collect specimens of rarely documented snakes and salamanders. I have also had the opportunity to photograph species, particularly salamanders, that previously lacked diagnostic photographs in life. Fieldwork in China presents unique logistical challenges, but these challenges only make the work more rewarding.

Chinese herpetology

Tracking down a short-tailed mamushi (Gloydius brevicauda) that escaped into thick vegetation

Collecting Hynobiid salamanders in western China

See more photos here:

Snake fungal disease in endangered Kirtland’s Snakes (Clonophis kirtlandii)

During my time in Indiana, I collaborated with the Indiana Department of Natural Resources and Dr. Drew Davis to sample Kirtland’s Snakes (Clonophis kirtlandii) for the fungus that causes snake fungal disease (Ophidiomyces ophidiicola). During the course of this project, we also collected genetic samples from all individuals and discovered new distribution records for C. kirtlandii, a species that is endangered throughout its distribution.